Introduction

“We want to put these data centres in space… There’s no doubt to me that a decade or so away we'll be viewing it as a more normal way to build data centres.”

Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, December 2025 (Fox)

To many, AI data centres in space may sound like a pie-in-the-sky idea. Yet, a growing number of tech titans, companies and nation states are increasingly viewing orbital data centres as a potential solution to rising energy and infrastructure constraints. The attraction lies in their access to near-constant solar energy, the absence of land and freshwater restrictions and insulation from grid bottlenecks that are already limiting AI data centre expansion on Earth. However, the hurdles to making space-based data centres economically viable at scale remain significant, with launch costs still needing to fall by more than 10x. As a result, space-based compute is not a near-term replacement for terrestrial infrastructure, but a potential longer-term solution, with economic viability most commonly estimated for the early to mid-2030s.

Figure 1: Paul Graham’s and Elon Musk’s exchange on the future of AI data centres

Source: X

In this note, we first examine SpaceX and its role as the primary enabler of the modern space economy. Next, we highlight a set of space data centre initiatives and assess the potential long-term benefits. We then outline the key challenges that must be overcome for space data centres to scale, alongside the early progress made by pioneers such as Starcloud, which recently trained the first AI model in orbit. Finally, we highlight some of the publicly listed companies that have exposure to this emerging field.

SpaceX

There has been a sharp acceleration in launch activity over the past decade, driven primarily by SpaceX. Founded in 2002 by Elon Musk, the company’s long-term objective was to make life multiplanetary. To pursue this long-term vision, SpaceX first needed to overcome foundational challenges of payload economics and operational scale, while also establishing a sustainable commercial business. A key pillar of this strategy has been to reduce launch costs by recovering and re-flying rocket boosters after launch, first achieved in 2016. This approach is now critical to SpaceX’s operating model, materially increasing launch cadence, lowering the cost per kilogram to orbit and underpinning a wide range of commercial activity in space.

Figure 2: FAA-licensed U.S. Orbital Commercial launches

Source: FAA

The focus on reusability and operational scale has culminated in the development of Starship, SpaceX’s next-generation rocket, designed to be fully reusable. Compared to the Falcon 9 rocket, which can deliver roughly 23 tonnes to low Earth orbit, Starship is expected to carry up to 150 tonnes when fully reusable (250 tonnes in an expendable configuration). This would represent a step-change in payload capacity and fundamentally alter the economics of deploying large assets in space. Starship flights are currently targeted for 2026, with Musk expecting this to increase SpaceX’s share of Earth’s total payload to orbit from around 90% to 98% over the next two years.

Figure 3: Starship

Source: SpaceX Instagram

In terms of financials, Musk has commented that SpaceX has been cashflow-positive for many years and that 2025 revenues were projected at US$15.5 billion. Of this, only US$1.1 billion is expected to come from NASA, with the largest revenue contributor being Starlink. Starlink is the company’s satellite constellation which delivers internet access across the globe, typically used in remote and underserved regions. It is also powering in-flight Wi-Fi for major airlines, including United Airlines and Qatar Airways, as well as Wi-Fi for cruise lines such as Royal Caribbean and Carnival.

Figure 4: Starlink data

Source: Starlink 2025 Progress Report

In 2024, Starlink also began deploying satellites with Direct-to-Cell capabilities, aiming ultimately to eliminate worldwide mobile dead zones. The service is currently available in 22 countries with 27 mobile network operator partners such as T-Mobile. Initial Direct-to-Cell capabilities have generally been limited to texting and certain apps, although functionality is expected to expand. Its next-generation Direct-to-Cell satellites will be launched by Starship and within two years it aims to deliver high-bandwidth internet enabling medium-resolution video streaming. This is being enabled by its US$17 billion purchase of spectrum from EchoStar, announced in September 2025.

According to a December 2025 article by Bloomberg, SpaceX is reported to now be targeting a potential US$1.5 trillion IPO in 2026, raising more than US$30 billion. This implies a roughly 100x revenue multiple on 2025 estimates, a valuation that embeds significant optimism around Starship, Starlink growth, and nascent opportunities such as space-based compute. Musk has linked valuation growth to advances in Starship, Starlink, and direct-to-cell spectrum, but to the best of our knowledge has not confirmed the valuation. Musk did however appear to indirectly confirm the IPO plans by responding that “Eric is accurate” on X to an article written by Eric Berger. The article argued that a primary rationale for going public would be to secure a substantial capital injection to fund the development of data centres in space.

A new era of data centres

“I think even perhaps in the four or five year time frame the lowest cost way to do AI compute will be with solar powered AI satellites.”

Elon Musk, SpaceX CEO, November 2025 (U.S.-Saudi Investment Forum)

Beyond SpaceX, interest in orbital data centres is expanding across both the technology sector and among governments. In November 2025, Google outlined plans under Project Suncatcher to deploy solar-powered satellites to house its tensor processing units (TPUs), with prototype launches targeted for early 2027. Eric Schmidt, former Google CEO, indicated that orbital compute formed part of the strategic rationale behind his investment in the rocket company Relativity Space. Nvidia is also investing in the sector by backing the startup Starcloud, which is building space data centres. Jeff Bezos, owner of the space company Blue Origin, has also endorsed the concept, commenting that there will eventually be giant gigawatt space data centres. China’s Zhejiang Lab is also pursuing orbital data centres, aiming to build a network of thousands of satellites to enable AI data processing, having already launched its first batch in May 2025.

Benefits

“We still don’t appreciate the energy needs of this technology…there’s no way to get there without a breakthrough…we need fusion or we need like radically cheaper solar plus storage or something at massive scale like a scale that no one is really planning for.”

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, January 2024 (Bloomberg, Davos)

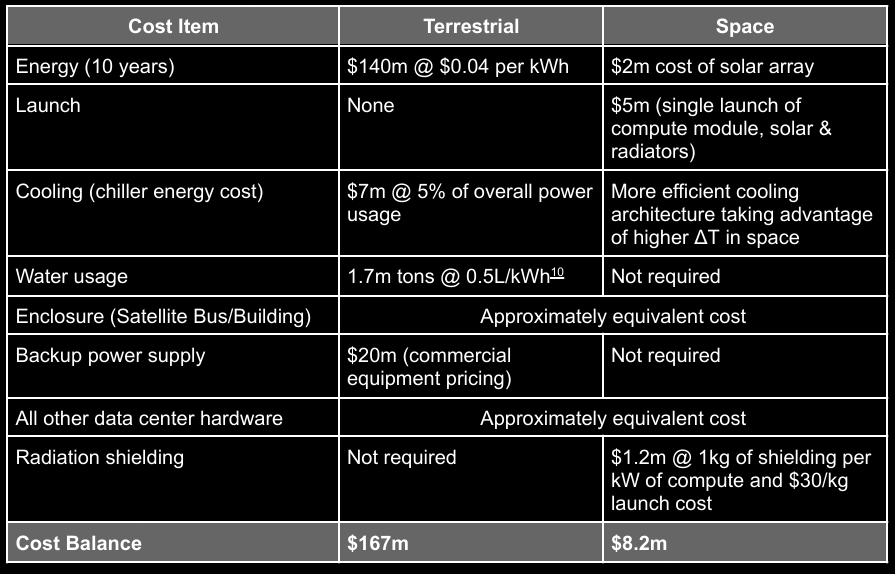

There are several compelling reasons to deploy data centres in space, but energy is the primary driver. AI data centres require vast amounts of power, currently placing significant strains on electricity grids and restricting future expansion. In space, however, data centres will have access to an abundance of solar energy as the satellites can stay exposed to nearly constant sunlight, unaffected by both weather and day-night cycles. This steady energy flow also removes the need for backup-power/batteries. Additionally, sunlight is stronger in space because there is no atmosphere to attenuate and scatter the solar radiation, resulting in peak power generation that is approximately 40% higher than on Earth, even on a clear day. Proponents estimate that solar panels in space could generate roughly 5x more energy than equivalent terrestrial arrays and, when comparing total system costs to prevailing grid electricity prices, it is estimated that energy costs could be around 10–20x lower.

Figure 5: Cost comparison of a single 40 MW cluster operated for 10 years in space vs on land

Source: Starcloud Whitepaper 2024

“The only cost on the environment will be on the launch, then there will be 10x carbon-dioxide savings over the life of the data centre compared with powering the data centre terrestrially on Earth.”

Philip Johnston, Starcloud CEO, October 2025 (NVIDIA blog)

Other benefits of space-based data centres relate to environmental impact. Due to its higher effectiveness, terrestrial data centres are increasingly shifting from air to water cooling, particularly in warmer climates. An EESI article reported that an estimated 80% of the water consumed in such systems is lost to evaporation. It also found that a single large hyperscale data centre may consume up to 1.8 billion gallons of water annually, equivalent to the needs of a town of 10,000–50,000 people. This can create significant pressure on local freshwater sources, such as rivers and aquifers, increasing risks for nearby communities. While the industry is evolving, with some operators deploying closed-loop cooling designs that materially reduce water consumption, locating data centres in space would still eliminate the need for water-based cooling altogether, reducing pressure on local water supplies. In addition, it would remove the need to acquire large areas of land and associated terrestrial infrastructure, while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Challenges and risks

While the theoretical benefits are compelling, the practical hurdles to achieving space-based data centres at scale are substantial and should not be underestimated.

The most significant barrier is launch costs. SpaceX currently charges US$6,500/kg. Starcloud estimates that launch costs will need to fall to US$500/kg before it can break even. Google estimates that launch costs will have to fall to US$200/kg before space data centres become comparable to those on Earth, and expects this to happen by the mid-2030s under the current trajectory. By contrast, Musk is more optimistic, with a 4-5 year timeline for when AI data centres become economically viable and is expecting to get launch costs down well below US$100/kg.

This divergence in timelines (mid-2030s versus 2029–2030) warrants scrutiny. Musk has a well-documented history of ambitious forecasting: Tesla's Robotaxi was originally promised for 2020, Full Self-Driving has been "one year away" for nearly a decade, and the Cybertruck shipped years behind schedule. Furthermore, the gap between US$6,500/kg today and US$200–500/kg required for viability represents a 10–30x reduction, a transformation that, even under optimistic assumptions, will likely take years to eventuate.

Another challenge is cooling. Space-based data centres cannot rely on terrestrial cooling methods and must instead dissipate heat through radiation. Heat is absorbed by a fluid and transferred to large radiator surfaces, which then emit it into deep space. These radiators must be substantial in size, making them a significant contributor to launch mass and cost, with meaningful design and manufacturing challenges.

Additionally, space does not benefit from Earth’s atmosphere, which helps shield electronics from harmful radiation. As a result, space-based data centres must incorporate mitigation measures such as shielding or error-correcting software to ensure reliable operations. Maintenance, logistics and regulation also remain meaningful hurdles. Unlike terrestrial data centres, failed components cannot easily be replaced or upgraded once deployed in orbit. In parallel, operators must manage orbital debris risk, navigate unclear data sovereignty and security frameworks for space-based compute and address concerns from regulators and astronomers around orbital congestion and interference with scientific observation.

Early progress

“Anything you can do in a terrestrial data centre, I’m expecting to be able to be done in space.”

Philip Johnston, Starcloud CEO, December 2025 (CNBC)

Despite these challenges, initial progress is already being made. In November 2025, Starcloud deployed the first Nvidia H100 GPU to space via SpaceX. In December, it was announced that it had trained the first LLM in space and had successfully run inference on it. The purpose was to prove that their thermal management and radiation shielding techniques allowed them to operate state-of-the-art in the harsh conditions of space. Going forward, Starcloud will continue to deploy more advanced satellites, with their second launch planned for October 2026, which will be at least 10x more powerful.

In their 2024 white paper, Starcloud outlined a vision for an eventual 5 gigawatt orbital data centre, with massive solar and radiators which would be approximately 4 kilometres in width and height. This equates to over 2000 football fields. However, the leap from a single GPU to a 5 GW orbital installation is immense, and investors should treat such projections as aspirational rather than operational guidance.

Figure 6: Illustrative concept of Starcloud’s proposed 5GW orbital data centre

Source: Starcloud

To the moon

“The Moon is a gift from the universe.”

Jeff Bezos, October 2025 (Italian Tech Week)

While initial orbital data centres rely on Earth-launched satellites, the ultimate vision extends to the Moon. Jeff Bezos has long advocated for moving heavy industry off Earth to preserve the planet, highlighting the Moon’s low gravity, proximity and resources for fuel and infrastructure. Additionally, President Trump’s December 2025 Executive Order calls for Americans to return to the Moon by 2028 and establish initial elements of a permanent lunar outpost by 2030. Musk’s longer-term ambitions aligns with this, envisioning factories on the Moon that use local resources to produce data centre satellites in vast quantities, potentially exceeding 100 terawatts of compute capacity. Due to the Moon’s low gravity, these satellites would be launched directly into orbit via mass drivers (electromagnetic railguns), dramatically lowering costs, enabling massive scale and unlocking a future of vast orbital AI compute.

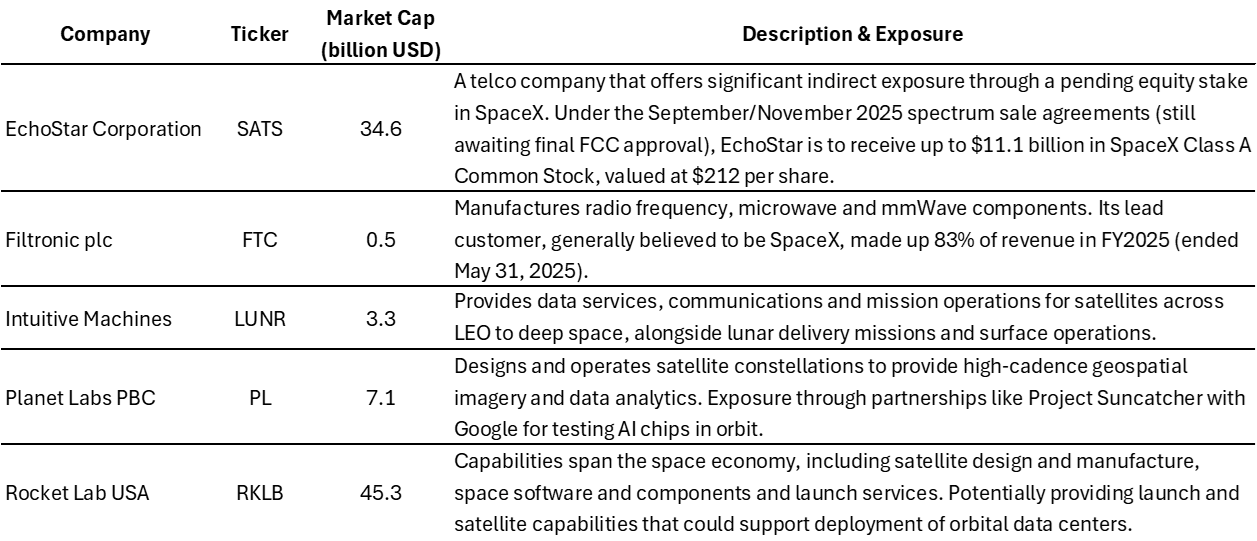

Listed companies in the space

Below we highlight some publicly listed companies that have direct or indirect exposure to space data centres.

Figure 7: Public companies with exposure to space data centers

Source: SimplyWallSt.

Note: Market cap.as of 9 Jan 2026

Conclusion

The concept of data centres in space is now moving from speculation to early experimentation as AI compute demand collides with hard, Earth-based constraints. While the challenges ahead remain substantial, with launch costs still representing a major barrier, early demonstrations and growing engagement from technology leaders and governments show this is no longer a fringe idea. However, this trajectory is not inevitable. Breakthroughs elsewhere could eliminate the need for space-based compute, whether through fusion delivering radically cheaper terrestrial energy or major gains in algorithmic or hardware efficiency. Yet, under today’s technological landscape, space-based data centres represent the most direct path being actively pursued to unlock the scale of energy required for future AI infrastructure.

At AlphaTarget, we invest our capital in some of the most promising disruptive businesses at the forefront of secular trends; and utilise stage analysis and other technical tools to continuously monitor our holdings and manage our investment portfolio. AlphaTarget produces cutting edge research and our subscribers gain exclusive access to information such as the holdings in our investment portfolio, our in-depth fundamental and technical analysis of each company, our portfolio management moves and details of our proprietary systematic trend following hedging strategy to reduce portfolio drawdowns. To learn more about our research service, please visit https://alphatarget.com/subscriptions/.